With the COVID-19 pandemic persisting for close to a year now, our daily routines and habits have changed dramatically. Those of us working from home have only a short commute from our beds to our desks, which may be convenient, but also reduces our exposure to different environments and blurs boundaries between work and leisure. Those who have lost their jobs or are shouldering childcare responsibilities on top of their work are facing numerous other challenges and changes to their lives, all of which may have lasting consequences. Most obviously, the change in routine due to public health restrictions has resulted in the visible dwindling of our social interactions. Could it be that the pandemic-related shift in our normal routines is also fundamentally changing the way we think and behave as human beings? It might be too early to tell but it’s definitely an interesting question to speculate about.

Understanding and measuring how the pandemic is changing our behaviour is difficult because it has impacted so many different domains of our lives. Not to mention, we are still in the thick of it, so we won’t know the lasting effects of the pandemic on human behaviour until it is long over. However, one can imagine possible effects on development, cognition, and socialization; domains that also interact with each other. What seems to weave many of these themes together is the need for novel experiences that allow us to learn about the world around us, whether it be meeting new people, developing friendships, or discovering new environments. All of these things are likely to affect us both emotionally and cognitively and are particularly important to consider in children, who are still learning social skills and how to navigate the world.

Changes in Development

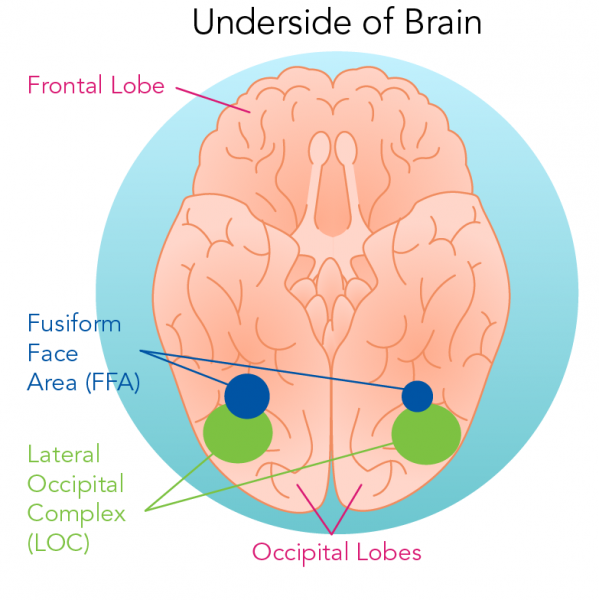

In the case of socialization, the rise of the pandemic has resulted in numerous shifts in our social behaviour: reduced social interactions, increased mask wearing, and greater interactions through computer and phone screens. The restrictions on normal social interaction may have significant long-term impacts on development. For example, our ability to read other people using subtle facial cues is obscured when they are wearing a face mask. Recognition of familiar faces is a process that children finish developing well into adolescence. A structure of the brain called the flexible fusiform area and surrounding parts of the temporal lobes are known to be involved in face recognition and processing of emotional cues.

Location of the Fusiform Face Areas and Lateral Occipital Complexes (image by VectorMine via iStockphoto).

The flexible fusiform area was once called the fusiform face area because it was first thought to specifically process faces. It was later discovered that the area also becomes activated when someone sees objects for which they have particular expertise. Given the ubiquity of human interactions, we are all experts in face processing, but this region also lights up when bird experts are shown different species of bird and for car aficionados when they see different car models.

Although there is debate about how much the ability to recognize faces is innate or developmental, research has demonstrated that brain regions become specialized with more exposure to stimuli in the world. During the pandemic, children and adolescents are interacting with their peers in a fundamentally different way that is largely virtual. As any Zoom user knows, even the best quality virtual interactions are very different from in-person exchanges, and, the benefit of ‘real time’ isn’t available to automatically detect subtle face cues.

On the other hand, and more optimistically, it is possible that the challenges of the pandemic will allow children to adapt by learning to recognize and read faces and emotions using fewer face cues, such as using the eyes and forehead in instances where people are wearing masks, and the tone of voice when video delays make facial cues harder to interpret. This is consistent with the knowledge that humans are excellent at adapting to environmental circumstances to perform similar functions using alternative strategies and that young brains are particularly plastic.

Under the current circumstances, technology is not only used for work and school-related meetings, but also for socializing with loved ones. Practicing physical distancing means that we are limiting interactions that involve physical touch, whether it be a handshake that symbolizes the start of a relationship or a hug, a high-five, or a friendly pat on the shoulder that lets others know we are there for them. Human touch is important for our mental health and wellbeing but exploring our other senses might be a unique way to make up for our touch deprivation.

Changes in boundaries of our sense of personal space, the buffer zone of safety surrounding our body, brings into question whether there will be shifts in our spatial awareness. The brain is responsible for computing our personal space, the boundaries of which can fluctuate according to our environmental context. For example, our personal space is reduced when we are among friends, but larger when we’re sharing a street with a complete stranger, yet somehow magically disappears when we need to get on an over-crowded subway!. Assessing one’s personal space involves attention and spatial awareness in order to monitor our environment and be ready to move away when someone intrudes into our space so that we feel safe.

But how do we modify our personal space when facing an invisible threat like this virus? It is again too early to predict the consequences of our spatial awareness as a result of the pandemic but what we do know is that our personal space has effectively been normalized across individuals to at least one meter in public (although the exact distance varies from country to country)

Limits to our Exploration

In addition to limited social contact, our freedom to explore our environment, whether it be through attending concerts and cultural events, checking out a new restaurant, or traveling to a new city or country, has been put on pause. How will these changes shape our cognitive processes?

One interesting example to think about is source memory, which is the memory for a personal event that is closely intertwined with the spatial and temporal details of the event. Many of our most memorable experiences are tied to distinct and novel environments, like when we visit a new museum or try a new sport. Now, a majority of our new experiences and memories are tied to one location: our home. What might the consequence of this be? Will it be more challenging to discriminate between different memories because they are tied to the same context?

Being exposed to new environments and engaging in social interactions provides novelty in a way that helps us pay attention. Difficulty focusing in online meetings has been reported widely and across many age groups. For young children and university students alike, online learning is challenging. Scientists have known for a long time that how we learn and recall knowledge is tied to the learning environment. If we associate our workplace (whether it’s an office or a café) with our occupation and our home as a place of relaxation, it naturally takes some time and effort to adapt when our home is suddenly also our workplace.

In many cases, the time saved by working from home has resulted in a misguided expectation of maximal productivity. We used to have time to think and reflect during the commute from home to work, or in the small nuggets of time spent travelling between in-person meetings. Now all of our meetings are held in one place and the transition time between one virtual room to the next is on the order of seconds. We are effectively Zooming (pun intended) from meeting to meeting, but time for idleness is also important for reflecting on events, ideas, and problems. Researchers have found that idleness and daydreaming – giving your mind the chance to wander – is crucial for creative problem solving. If we really want to make the most of our new work environment, we should make sure to also schedule time during which we can switch off.

Humans adapt (consciously and subconsciously)

It is important to remember that the restrictions on our freedom to explore the world do not necessarily mean that our experiences must be limited as well. For many, more time at home has provided an opportunity to learn new skills, such as cooking or playing an instrument, or to explore a new world through a book or movie. With Netflix’s release of The Queen’s Gambit, chess boards are being sold in record numbers, illustrating the desire of housebound people to expand their minds and find new ways to challenge themselves. These types of experiences can stimulate minds in a way that diverse environments used to. For example, although we are not practicing spatial memory by physically navigating new places, we have infinite possibilities of mentally navigating 16 chess pieces on an 8×8 square board to finesse our pattern recognition abilities. While we are missing the opportunities that we sought out pre-COVID, we are not banned from engaging in the experiences that enrich us as human beings.

One thing the pandemic has shown us is that humans are incredibly good at adapting to challenges – that is what makes us resilient. The closure of gyms has allowed us to find new ways to exercise outdoors and attend online yoga classes. We are finding innovative ways to celebrate special occasions, such as the Hindu festival of Diwali (the triumph of good over bad), Thanksgiving, and the holiday season. What it has also shown us is that we have to work together and find creative ways to get through this pandemic. For a bit of hope and inspiration, take a look at this Twitter thread by an employer who acknowledges the difficulties that women in the workplace face during the pandemic. His words show support for his employees during these challenging times and are a good example of what can be done to counteract this disheartening reality:

We have all been adapting based on the constantly evolving knowledge about the pandemic while we await the advances in science and medicine that will shape our lives in the coming days and years. Despite the pandemic-related fluxes and limits to exploration, we have lived through massive world events before, and despite consequences, the resilience and adaptability of human nature always persists. Whatever consequences there may be on our cognitive, social, and emotional processing, our brains are built to help us through. Who knows, maybe we’ll even learn some important lessons that we can bring into a post-COVID era that ultimately works towards a more inclusive and welcoming world.

Sivaniya Subramaniapillai completed her PhD in Experimental Psychology at McGill University in 2021. Her research aims to characterize brain-aging trajectories of women and men and understanding the lifestyle factors that contribute to healthy aging. Sivaniya is excited about fostering scientific dialogue between the research community and the public in a way that promotes greater inclusivity and public engagement. To sign up to her personal newsletter, please visit http://sivaniya.beehiiv.com/.

Interesting post, thanks for sharing.