Video games are more popular and more profitable than ever before. Having come a long way since the arcade hits of decades past like Pong and Pac-Man, modern video games often have incredible photorealistic 3D graphics as well as complex narratives and engaging storylines that have helped them outperform even cinema in terms of profit and share of the entertainment industry. Video game players get to become part of the narrative by virtually embodying characters through gameplay, which often runs for over 20 hours or more, rather than just observing the story from the outside for 1-2 hours of film. As a result, people often report that video games can to some extent elicit far stronger emotional responses than movies, making it somewhat unsurprising that many games end up with cult-like followings of devoted fans waiting anxiously for the next release.

The general assumption made by both video game producers and computer hardware manufacturers is that more refined graphics will lead to more emotional engagement in the game. While this is certainly true for scenery, objects, and even the costumes and hairstyles of characters, there may be an interesting exception to the rule when it comes to faces. I am a gamer myself and when a character cries, I rarely feel truly emotional for them even though I’m a true weeper when it comes to some very cartoony movies. I decided to take a closer look at why this might be the case and whether I’m really an outlier in my apparent immunity to video game-induced emotions. Am I the only one who just feels kind of creeped out when I see a photorealistic 3D-animated face getting emotional on my screen, or is there a scientific reason that both real-life humans and cartoon characters can make me cry but a life-like animated person can’t?

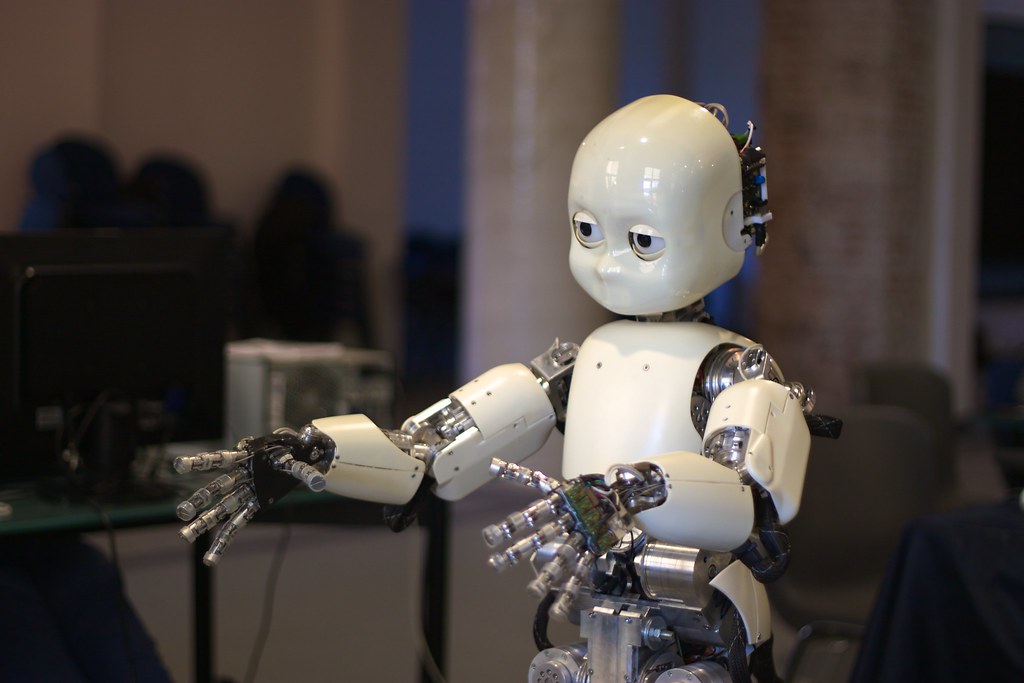

Enter the uncanny valley. You may have heard of this phenomenon in the context of humanoid robots, for which it was originally coined, but it applies equally well to computer generated characters such as those in video games.

As can be seen on the graphic below, the affinity we feel towards any artificial character (robot or animation) gradually increases as human likeness goes up. Interestingly, once likeness reaches a high percentage, there is a dramatic dip in affinity, known as the uncanny valley. Both highly realistic humanoid robots and photorealistic animated faces fall into this valley and are often described as eerie, unsettling, and even creepy.

Well, this is very cool, but it’s only a thought experiment and it describes only subjective feelings of affinity. Rest assured, some very interesting quantitative research has been done on this topic examining how our brains respond to computer generated faces relative to pictures of real human faces.

One research team decided to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to see if animated computer-generated faces could enhance brain activity associated with emotional processing in the same way as real facial movements/expressions. They found that both types of faces generated similar activity in the amygdala, a brain region that responds to emotional stimuli. The amygdala is very sensitive though, and it also acts as a sort of alarm system that helps us detect threats and exciting things around us. This explains why even the uncanniest of computer-generated faces might set off the amygdala and suggests that its activity alone is not enough to explain the uncanny valley phenomenon. Interestingly, when the researchers asked the participants to rate the emotional intensity of the presented faces, it turned out that emotional faces from real human beings did in fact trigger stronger emotions than those modelled with a computer software. Why didn’t this difference show up in the brain activity? Well, the subjective feeling of emotional intensity is actually a much more complex process than the instinctive threat-detecting role of the amygdala and likely involves many more networks and regions of the brain that this study did not look at.

Another exciting way to look at emotional processing in the brain is using electroencephalography or EEG. EEG is a bit like a blurry video camera: It allows us to see in real time the electrical activity occurring in the brain, without necessarily knowing precisely where the activity is coming from. This can be very insightful because it allows us to document the timeline of different cognitive activities that can’t be measured otherwise. When it comes to the brain’s reaction to emotional faces, the results are very interesting. It seems that cartoony faces can elicit emotions, but they do so specifically at the first glance. After a while, the emotional response is higher for photorealistic faces and real faces than for cartoony faces. One possible explanation for this is that more detailed faces require more time to be fully perceived, which may lead to a prolonged emotional processing. Further, faces that look either very cartoony or very realistic seem to create the same activity related to facial processing. Photorealistic faces are therefore not exactly processed the same way as real or cartoon faces. Both can provoke emotions, but not necessarily for the same reasons.

So, how can we explain the uncanny valley? Well, as I tried to illustrate, there are similarities and differences in our reactions to real and computer generated faces. If we talk about very early instinctive reactions, well, the uncanny valley is not relevant, but if we consider more complex emotional processing, then it is. Our brains are very good at detecting that any presented face is not a “real” one, which might impede how engaged we are emotionally with computer-generated characters. However, this doesn’t mean that a computer can’t move us. There is much more to our emotional response to an animated film or game than just faces, and plenty of other factors might compensate for the uncanny valley. Sometimes, a good voice actor can make us feel strong emotions and on other occasions, an engaging scenario can trigger relatable emotional involvement. The uncanny valley can affect our emotional engagement, but we must not forget that entertainment is complex and rests on multiple dimensions. So to revisit the question famously asked by EA Games in the 1980s, can a computer make you cry? Probably, at least if it provides you with more than just a creepy face.

Gasser is a Ph.D student in clinical neuropsychology at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières under the supervision of the Professor Simon Rigoulot and the Professor Isabelle Blanchette. His main research interests revolve around affective neurosciences. Precisely, He is using EEG in order to uncover the cognitive activities implied in the emotional information processing.